The following text is an excerpt from “Towards an Ecology of Care: Basic Income Beyond the Nation-state (unpublished). Even though the degrowth movement has shown the limits of our civillization’s obsession with growth, and has promoted and proposed complementary currencies, the degrowth critique has yet to consider the role that money/credit creation plays more explicitly. Ecological economics has still to develop a monetary theory of its own, as well Our call for an ecology of care aims at outlining the relationship between growth and monetary creation, and to lay the foundation of what we call degrowth money. We argue that money’s ‘nature’ itself also has to be changed and expanded in order to avoid the growth imperative from destroying the diversity of the world’s ecosystems. Silvio Gesell is considered to be the first person in the modern era to develop the idea of free money (freigeld), where money would “rot like potatoes, rust like iron and evaporate like ether”. The notion of a rotting money or to “make money worse as a commodity if we wish to make it better as a medium of exchange” was later termed demurrage. Embedding Gesell’s decaying free-money within the degrowth framework, we argue that a degrowth money can help us solve our current economic, social and ecological crisis for the following four reasons:

1. Time Horizon: The way the money system works today affects our time horizon, as the short term is valued over the long term. Any investment which provides profit faster is given priority over long term production and planning. Because money today is made scarce through the production of credit, people have to compete over the interest in labor markets, making humanity’s time on earth an endless cycle of debt. In contrast, demurrage or degrowth money incentivizes long term decision making via discounted cash flows. Demurrage is a way of going slow, valuing the long term present value of things over the short term. Using the words of an economist, we have a situation where money has a negative interest rate embedded in its design.

2. Liquidity Trap: Modern central banks are theoretically responsible for setting interest rates and managing the supply of money, in order to control inflation. These are the initial conditions which private banks use to issue credit to people. But as it is widely known, capitalism is prone to boom and bust cycles. A liquidity trap is a term economists use to describe the situation when money in an economy stops circulating regardless of the actions of central banks to increase the supply of money and affect interest rates. As trust in the economy disappears and a financial crisis starts, people start to hoard any money they can get their hands on. Degrowth money solves the liquidity trap by putting a limit on the amount of time that money can carry value. As complementary currency expert Bernard Lietaer put it, it is like charging ‘a parking fee on money’. Because people do not want their money to decay, they start to circulate it, as the many historical experiences during the Great Depression demonstrate.

3. Integrating Entropy: We know from thermodynamics that energy can neither be created nor destroyed, just transformed. Degrowth money integrates the second law of thermodynamics into monetary theory by designing a money that is meant for circulation rather than accumulation. Money today expands through bank credit creation. Debt produces a vacuum for the extraction of value which sucks wealth back into the hands of the lender at the expense of the planet’s resources and most of humanity’s labor power. The accumulation of wealth made by our current systems of production implies the production of a lot of waste, or energy that irreversibly increases the total level of entropy of the planet. Increasing levels of (compounded) interest in money thus increase the entropy levels of the planet, which in turn lead to an overshooting of our planetary boundaries and the useful energy needed to reproduce life. Put more simply, wealth is waste. By making the value of money have a life-span, a degrowth money system has the potential to change the way energy is distributed and reintroduced within the system (and hence reduce its waste). This not only increases perceived wealth due to the higher velocity of money in circulation but also makes the deterioration of the quality of energy (entropy) slow down.

4. Ending the Material Growth Imperative: The way money is designed today favors money lenders and money holders. Positive interest on credit creation necessarily leads to more economic growth. A degrowth of money would stop the imperative to increase our material output as the effective interest rate on a yearly basis is zero or negative in comparison to previous years, instead allowing for qualitative growth in individuals and communities alike. As Gesell himself put it: “Supply is something detached from the will of owners of goods, so demand must become something detached from the will of owners of money”. Detaching demand from the owners of money allows for complementary monies to be used for investment in local infrastructure, basic services, health and education. Degrowth money is fundamentally a different type of money which has the potential to make our human ecosystem more resilient as a whole through the introduction of monetary diversity, separating money’s functions in multiple money forms.

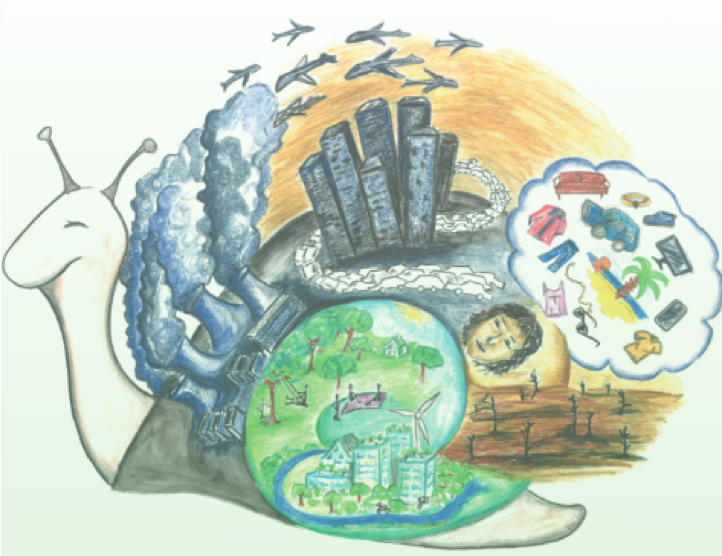

As social ecologists remind us, the very notion that men can dominate nature is rooted in the real domination of men over other men and over women. While the planet’s biosphere might recover without us as a species, we will not recover without the biosphere. The extraction of nature’s resources for the sake of short term profit and people’s capacity to reproduce and produce their life is organized by how money works. The ecology of money today is thus one of a monoculture, where we use the same type of money to arrange everything in our lives, from education to housing to the marketplace. While it might be efficient, a money system without a break or escape valve is dangerous as it makes the system in which we live very rigid and fragile. Just like red blood cells which are created in the bone marrow with the purpose of supplying the entire body with nutrients, which then die and are discharged with time, so should money also help to nurture people’s social reproduction and decay when not in use. Instead of private banks creating most of the money supply as an interest-bearing monoculture which extracts the yield of living ecosystems, we should think of money’s transformation in holistic ways. We should embed the principles of localism, self-sustainability, decentralization and confederation into our systems of production, distribution and the democratic organization of the institutions that take care of life. The ecology of care thus aims at people-powered-money, issued unconditionally with the goal that income is divorced from work and people do not have to rely solely on a wage in order to get what they need to reproduce their daily life. This Basic Income is distributed as a share of the yield of the wealth held in common. The issuance level necessary for people to have self-reliance should be decided democratically and it should be equivalent to the cost of the material conditions needed to meet and complement people’s basic needs in their region. Making money alive through demurrage means that money will also gradually die when not in use. Degrowth money allows us to limit the extent to which accumulation can take place in the system and instead foster circulation and exchange within the values of the commons. Like this, both the issuance and the decay of money take place constantly and adapt to the seasonal needs of people who govern it, following the principles of the commons outlined by Östrom and others. A currency that decays requires us to rethink the whole structure of the interdependent social relations which keep the economic, biophysical, and social systems together. The ideas of the degrowth literature share an expansive notion of care, in the sense that the provision of social care cannot be detached from the care of nature and its regenerative limits. Degrowth requires the care of our environment in harmony with the care of people; to go beyond ‘the illusion of an independent human existence’, both independent of other people and of the worlds we form part of. This intertwined human condition becomes clear when we try to figure out how to take care of people at a practical level: we understand that no care is possible in a destroyed, biodiversity poor and polluted environment. People are, after all, part of their ecosystems. We suggest a degrowth money to move towards this utopia.

Saturday 1st June 2019 marked a significant occasion for the degrowth movement: the inaugural ‘Global Degrowth Day’. Groups of people gathered together in places all around the world to engage with ideas of degrowth and alternatives to our growth-based society, guided by the event’s theme of ‘a good life for all’. The Global Degrowth Day was coordinated by the Activists and Practitioners int...

Degrowth stands for moving beyond the paradigm of the growth- and profit-oriented economic system. By means of a social-ecological transformation, a good life for all can be achieved. This means overcoming the imperial way of living of the global North, building alternatives, and creating positive narratives of our possible future. This also includes resisting useless large-scale projects, priv...

On 14 March the last submission period closed for contributions to the conference. After a first quick review it was already clear that all expectations were far exceeded: more than 350 scientific papers were received from a broad range of disciplines such as economics, psychology, geography and urban planning. Further 260 proposals for practice-based activities were submitted by various civil-...